|

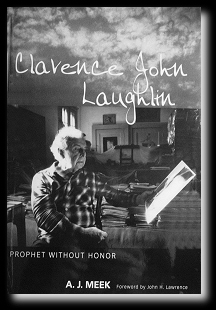

Clarence John

Laughlin Clarence John

Laughlin

Prophet Without Honor

A. J. Meek, with a foreword by John H. Lawrence

REVIEWS

THE TIMES

PICAYUNE

Clarence Through a glass

darkly

Sunday, March 11, 2007

By Susan Larson

"In old grimy streets, in isolated and decaying houses, sometimes

far from the Vieux Carre, in little used and secluded cemeteries,

there still sluggishly circulates the ebbing blood of the past, of a

vigorous and vividly hued past." -- Clarence John Laughlin

New Orleans breeds eccentrics -- sometimes elevating them to cult

status, sometimes neglecting them entirely. In "Clarence John

Laughlin: Prophet without Honor," photographer and Louisiana State

University art professor emeritus A.J. Meek gives us a fine portrait

of one of the city's best known characters, photographer Clarence

John Laughlin. Laughlin (1905-1985) is today most remembered for his

classic work, "Ghosts Along the Mississippi," photographs of the

vanishing plantations along the River Road, originally published in

1948 and reprinted many times since.

Meek paints a fascinating portrait of the Lake Charles native, who

was a boy of 14 when his father died in the great flu epidemic of

1918. With a grieving mother and a crippled sister to support and

care for, Laughlin's family life was demanding to say the least; his

life would follow a pattern of responsibility and flight. He would

marry five times -- twice to the same woman, Elizabeth Heintzen --

and he would not know his three children well during his lifetime.

Laughlin was an artist first and foremost. He began his professional

life as a clerk at Whitney Bank, but took correspondence courses

from LSU; in the '30s he began taking photographs and worked for the

Army Corps of Engineers, spending considerable professional time

photographing the construction of the New Orleans levee system. His

life would be a difficult balancing act of creative and commercial

work, of trying to make a living and see his vision through.

He met many of the noted photographers of his era, a time during

which photography came into its own and achieved great popularity.

Laughlin met Edward Weston, Ansel Adams, Minor White, the wonderful

Imogen Cunningham (who once served him bonbons and sherry in a

mischievous joke about how Laughlin thought he deserved to be

treated like a king -- although he didn't quite get the joke). He

would have disastrous arguments and longstanding feuds with most of

them, especially the powerful Edward Steichen.

New Orleans itself would be Laughlin's muse -- he photographed the

city's nooks and crannies, capturing or creating unusual scenes

rather than the standard romantic images. Influenced by the

surrealists, he assembled his own visionary and poetic reality and

vocabulary, always insisting on writing long explanatory captions

himself. These captions often became a source of contention with

editors and curators of his work.

His working conditions were difficult. Thanks to the generosity of

Edgar Stern, he was the beneficiary of an unusual arrangement:

Laughlin worked in a darkroom in the basement at Longue Vue while

the Stern family slept, trudging and schlepping supplies back and

forth from his apartment at the Pontalba as well as other residences

throughout the city on public transportation. (Laughlin didn't

drive, and resisted much of 20th century technology.) Finally he

settled in the Marigny near the end of his life, when he and

Elizabeth reunited in his fifth, and final, marriage.

In 1981, the Historic New Orleans Collection acquired Laughlin's

archive of photographs, correspondence and writings, both published

and private, and curator John Lawrence's wonderful foreword

describes a meaningful moment shared with the photographer. Meek has

made fine use of this remarkable material, often letting his subject

speak for himself in that distinctive and assertive voice. Readers

grow to understand the difficulties of his life, both personal and

professional, and see to what extent his prickly personality lay at

the root of those problems.

There are reproductions of 40 photographs included, complete with

Laughlin's idiosyncratic captions, and Meek illuminates each image

for the reader, describing its creation and its personal meaning for

the photographer.

One wishes for a bit more literary context for Laughlin's work -- we

learn that his library was his great pride, and seemed at times to

be regarded as one of the mysterious treasures of the city, but we

don't learn much about Laughlin's reading, except for "Aesop's

Fables," the tales of the Brothers Grimm, the work of the

philosophers Nietzsche and Schopenhauer, and the French symbolists,

particularly Charles Baudelaire. (Laughlin would finally travel to

Baudelaire's grave in the Paris cemetery of Père-Lachaise near the

end of his own life; his final resting place is in the same

cemetery.) But there are tantalizing references -- a letter to

science fiction writer Fritz Leiber, a planned visit to Ray

Bradbury! -- that are left unexplored. And that magnificent library

was dispersed throughout the libraries of Louisiana State

University, rather than being left intact, as Laughlin had hoped.

Toward the end of his life, Laughlin began to receive some of the

recognition he deserved; Meek recounts his acceptance of an honorary

degree from Tulane University -- complete with a complaint about the

"absurd attire" required for the occasion, strangely endearing and

perfectly characteristic.

In one of his final writings -- a note composed during his final

stay in Touro Infirmary, Laughlin summed it up:

"I have opened the doors of the world that we know and have found a

world so fantastic, so incredible that it constitutes a new mode of

existence -- a new kind of reality.

"The fused magma of reality created a fairy tale reality world --

which had the scent and texture of melted dreams and the hues of

soluble visions."

Meek, in this admiring yet clear-eyed biography, makes us see the

man behind those melted dreams, appreciate his achievements as well

as his shortcomings, in a welcome look at a true New Orleans

original.

THE

ADVOCATE

Reviewed by GREG LANGLEY

Books editor

Clarence John Laughlin wanted to be a writer but worked in a bank,

began his artistic career as a painter but is best known for his

photography. The life of this enigmatic New Orleanian is the subject

of Clarence John Laughlin: Prophet Without Honor (University Press

of Mississippi, $30).

The book is by A.J. Meek, professor emeritus of art at LSU. Meek

combines biography and criticism with reproductions of some of

Laughlin’s black and white photographs to explain the artist’s

complex creations. Early on, Meek says, Laughlin showed his maverick

streak.

“He refused to photograph the usual beautiful locations of the

French Quarter (Vieux Carre) and make the typical tourist snapshots,

focusing instead on the overlooked Quarter architecture.”

Laughlin began with a documentary style that informs his

“masterwork” — Ghosts Along the Mississippi — originally published

as a magazine piece in Harper’s Bazaar and later expanded into a

full-length book in 1948. Laughlin’s compositions with disparate

elements and his use of double exposures and darkroom techniques

imbued his photographs with an otherness that earned him the title

of father of American surrealism. But Meek makes it clear that no

label can completely encompass the work of this prolific artist.

Meek writes with a factual, academic style that is surprisingly

lively. His subject is partly responsible for that. Laughlin, who

died in 1985, was a bright light who would bear no pale description.

Readers with an interest in the arts, in photography and in

Louisiana will find this book engrossing, entertaining and, perhaps,

inspiring.

THE MOBILE REGISTER

Reviewed by John Sledge

A clear look at photographer

Laughlin

Sunday, April 15, 2007

ewas by turns domineering, opinionated, tedious and fussy, but he

was also undisputedly a genius. New Orleans photographer Clarence

John Laughlin (1905-1985) may have been difficult to like, but his

life and significance as a surrealist American artist have long

deserved competent analysis.

Happily, this has now been provided in "Clarence John Laughlin:

Prophet Without Honor" (Mississippi, $30) by A. B. Meek, professor

emeritus of art at Louisiana State University and the author of

several previous books on cultural matters. In 200 pages of

footnoted text, Meek presents an unvarnished but balanced and deft

overview of his prickly subject, a man once hailed as "Edgar Allan

Poe with a camera."

Luckily for this project, Laughlin left an enormous collection of

prints, negatives, articles and correspondence. "The sheer volume of

the Laughlin papers is enormous," Meek writes. "In the history of

photography, I know of no one, except perhaps Ansel Adams, who

produced more than Laughlin." Meek quotes from these papers

extensively, as he should, for Laughlin thought long and deeply

about his craft and was vitally concerned with how future historians

would evaluate him. Meek is right to question Laughlin's positioning

of his work, however, writing that what he "had to say about his

photographs ... seems at times to defy historical analysis."

Meek heightens the reader's interest with 40 well-chosen

black-and-white illustrations, including reproductions of Laughlin's

stunning photographs and, most touching, a shot of the

septuagenarian master at rest in a Magazine Street gallery, looking

anything but cantankerous.

But as Meek makes abundantly clear, Laughlin was pig-headed to a

fault. He could not resist long political tirades when invited to

speak in university settings, alienating audiences that were

prepared to like him. As one observer wryly remarked, "He was not

his own worst enemy, but his own assassin."

Laughlin is best known for his 1948 book, "Ghosts Along the

Mississippi," which to date has sold over 100,000 copies. If

mystified by his lengthy, loopy philosophical captions, the public

was thoroughly beguiled by his large-format, black-and-white

photographs of abandoned Louisiana plantation houses. Not content to

simply shoot these elegant ruins, Laughlin used dark-robed and

veiled female models to powerfully emphasize themes of social and

moral decay. His success at making his pictures, captioning them the

way he wanted (mostly), and selling them to the book-buying public

certainly commands respect. And the historic preservation movement

benefitted enormously from the greater awareness and sense of

outrage that Laughlin created for the loss of these old treasures.

However, according to Meek, Laughlin continually sabotaged himself

with publishers, editors (including Maxwell Perkins) and fellow

artists. The wonder is that he got anything before the public at

all. During the production of "Ghosts," he whined so much about

retaining control over photographic reproduction and his

incomprehensible, rambling prose that an exasperated Perkins wrote,

"... we are not just printers to whom an author can specify the way

in which he wishes his book to appear."

Even erstwhile friends could find themselves on the receiving end of

hysterical assaults. Minor White, the editor of Aperture magazine

and a great believer in Laughlin's images, learned this in 1956. At

issue, as was usually the case between Laughlin and those attempting

to showcase his work, was White's insistence that the photographer's

verbose captions be cut. Laughlin exploded, and a series of angry

letters ensued. Finally, to a hurt White he harrumphed:

"Incidentally, I don't think you a bastard -- I think you a

politician. (Which, in my estimation, is worse). In other words, you

are a politician who knows exactly who the 'important' people are,

what to say about them, and their friends, and also, exactly who can

be of help to you in making a living."

Not surprisingly, Laughlin's personal life was also stormy. He

married five times, twice to the same woman, Elizabeth, and only

seems to have found some measure of domestic bliss with her towards

the end. Meek is mostly silent about Laughlin's two children, and

one wonders what remains unexcavated there. That he was a distant,

if not mostly absent father, seems clear.

If he were alive today, Laughlin would probably hate this book. Yet

Meek lets him have his say in these pages, to both good and ill

effect, and in the end securely situates him within the frame of

modern art history. That is a service for which the old man's shade,

surely knocking about the French Quarter somewhere, should be

eternally grateful.

Purchase a copy of this book.

HOME I

BIOGRAPHY I

GALLERIES I

BOOKS I

LINKS I

CONTACT

|